Reading Passage 2

TWO WINGS AND A TOOLKIT

A research team at Oxford University discover the remarkable tool making skills of New Caledonian crows.

Betty and her mate Abel are captive crows in the care of Alex Kacelnik, an expert in animal behaviour at Oxford University. They belong to a forest-dwelling species of bird (Corvus moneduloides) confined to two islands in the South Pacific. New Caledonian crows are tenacious predators, and the only birds that habitually use a wide selection of self-made tools to find food.

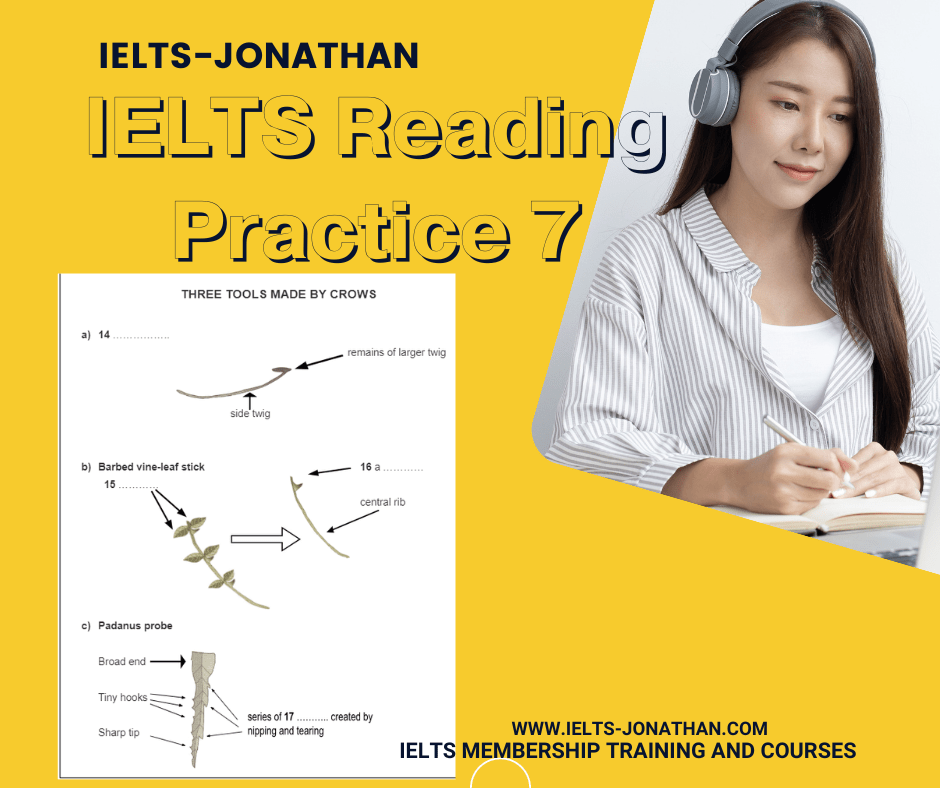

One of the wild crows’ cleverest tools is the crochet hook, made by detaching a side twig from a larger one, leaving enough of the larger twig to shape into a hook. Equally cunning is a tool crafted from the barbed vine-leaf, which consists of a central rib with paired leaflets each with a rose-like thorn at its base. They strip out a piece of this rib, removing the leaflets and all but one thorn at the top, which remains as a ready-made hook to prise out insects from awkward cracks.

The crows also make an ingenious tool called a padanus probe from padanus tree leaves. The tool has a broad base, sharp tip, a row of tiny hooks along one edge, and a tapered shape created by the crow nipping and tearing to form a progression of three or four steps along the other edge of the leaf. What makes this tool special is that they manufacture it to a standard design, as if following a set of instructions. Although it is rare to catch a crow in the act of clipping out a padanus probe, we do have ample proof of their workmanship: the discarded leaves from which the tools are cut. The remarkable thing that these ‘counterpart’ leaves tell us is that crows consistently produce the same design every time, with no in-between or trial versions. It’s left the researchers wondering whether, like people, they envisage the tool before they start and perform the actions they know are needed to make it. Research has revealed that genetics plays a part in the less sophisticated toolmaking skills of finches in the Galapagos islands. No one knows if that’s also the case for New Caledonian crows, but it’s highly unlikely that their toolmaking skills are hardwired into the brain. ‘The picture so far points to a combination of cultural transmission – from parent birds to their young – and individual resourcefulness,’ says Kacelnik.

In a test at Oxford, Kacelnik’s team offered Betty and Abel an original challenge – food in a bucket at the bottom of a ‘well’. The only way to get the food was to hook the bucket out by its handle. Given a choice of tools – a straight length of wire and one with a hooked end – the birds immediately picked the hook, showing that they did indeed understand the functional properties of the tool.

But do they also have the foresight and creativity to plan the construction of their tools? It appears they do. In one bucket-in-the-well test, Abel carried off the hook, leaving Betty with nothing but the straight wire. ‘What happened next was absolutely amazing,’ says Kacelnik. She wedged the tip of the wire into a crack in a plastic dish and pulled the other end to fashion her own hook. Wild crows don’t have access to pliable, bendable material that retains its shape, and Betty’s only similar experience was a brief encounter with some pipe cleaners a year earlier. In nine out of ten further tests, she again made hooks and retrieved the bucket.

The question of what’s going on in a crow’s mind will take time and a lot more experiments to answer, but there could be a lesson in it for understanding our own evolution. Maybe our ancestors, who suddenly began to create symmetrical tools with carefully worked edges some 1.5 million years ago, didn’t actually have the sophisticated mental abilities with which we credit them. Closer scrutiny of the brains of New Caledonian crows might provide a few pointers to the special attributes they would have needed. ‘If we’re lucky we may find specific developments in the brain that set these animals apart,’ says Kacelnik.

One of these might be a very strong degree of laterality – the specialisation of one side of the brain to perform specific tasks. In people, the left side of the brain controls the processing of complex sequential tasks, and also language and speech. One of the consequences of this is thought to be right-handedness. Interestingly, biologists have noticed that most padanus probes are cut from the left side of the leaf, meaning that the birds clip them with the right side of their beaks – the crow equivalent of right- handedness. The team thinks this reflects the fact that the left side of the crow’s brain is specialised to handle the sequential processing required to make complex tools.

Under what conditions might this extraordinary talent have emerged in these two species? They are both social creatures, and wide-ranging in their feeding habits. These factors were probably important but, ironically, it may have been their shortcomings that triggered the evolution of toolmaking. Maybe the ancestors of crows and humans found themselves in a position where they couldn’t make the physical adaptations required for survival – so they had to change their behaviour instead. The stage was then set for the evolution of those rare cognitive skills that produce sophisticated tools. New Caledonian crows may tell us what those crucial skills are.

Questions for this text

My Advice is:

Use the strategies I have discussed to make your reading for information more effective.

It IS a good idea to look at the questions for each passage before you start reading, but don’t spend too long on this. Just notice any key words, terms or names and important dates or numbers.

Then read the passage…..

Don’t read for detail. – Read to gain an overall understanding of the organisation of the text and how it develops and arrangement of ideas.

Next go to the first Question. Read the question, identify the task and consider the information you are looking for.

Skim read the passage to locate the area you are likely to find the information you need (remember that some questions follow the order of the passage) and then scan, before reading in detail and checking your answer.

Then do the same for the remaining questions

At the end, when you check your answers, think carefully why you got some answers wrong and why some sections were challenging.

Was it your understanding of the text or the reading strategy you followed?

Jonathan

———-